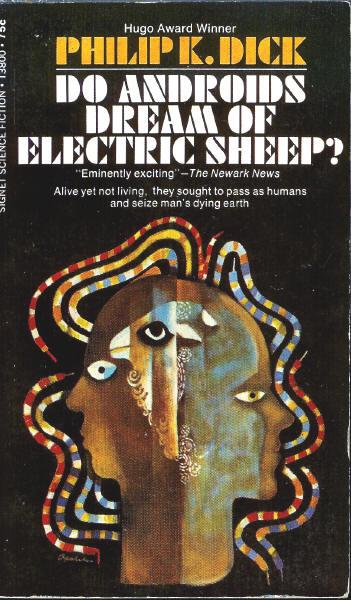

Most novel-to-screen adaptations have interesting paths that they follow in developing a story from something that works on the page to what makes a compelling movie. Blade Runner, adapted from Phillip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, is no different…

The path to adapting Dick’s novel – one of the scifi novelist’s most beloved tomes, alongside The Man In the High Castle and A Scanner Darkly – was a meandering one from its publication in 1968. Martin Scorsese was interested for a while, but never optioned it; meanwhile, Dick hated the first treatment by screenwriter Robert Jaffe. Eventually, writer Hampton Fancher (who has also returned for the upcoming Blade Runner: 2049 follow-up) wrote a draft in 1977 that would be rewritten and adapted into Ridley Scott’s film. Dick approved of the shooting script, however he would never get to render his final verdict on the result; the novelist died tragically of a stroke at the age of 53, just three months before Blade Runner was released in theaters.

The underlying themes of Blade Runner – what is it that ultimately defines us as human, and is it quantifiable by how we were created or something more profound? – have a lot in common with the book. Yet as is often the case with novel adaptations that make the film medium entirely their own, there are a lot of differences between Dick’s creation and the film that Fancher and Scott finally realized. Here are a few of the interesting ones:

The underlying themes of Blade Runner – what is it that ultimately defines us as human, and is it quantifiable by how we were created or something more profound? – have a lot in common with the book. Yet as is often the case with novel adaptations that make the film medium entirely their own, there are a lot of differences between Dick’s creation and the film that Fancher and Scott finally realized. Here are a few of the interesting ones:

The Title (duh): The most obvious one, certainly, but how that title came about is a bit unexpected. Blade Runner isn’t just a phrase that Fancher made up to replace the futurist query of the original title; he borrowed it from a completely different book. The Bladerunner is a 1974 novel by Alan E. Nourse about a futuristic black market for medical services in a dystopian society focused on eugenics. After going through the titles Android (boring!) and Dangerous Days (Sounds cool, but what does it mean?), Scott bought the rights to the name and Fancher used it to re-title not only their film but their lead character’s occupation. (In Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Deckard is simply referred to as a bounty hunter.)

“Andies” vs. “Replicants”: The word “replicant” as a term for a synthetic human has become so iconic as part of Blade Runner‘s contribution to sci-fi vernacular, even appearing as a dictionary definition in the first few moments of the film’s opening sequence. However, it’s not a term that appears in Dick’s novel at all; as stated in the title, they’re called androids in the book though the slang term “andies” appears frequently. “Replicants” as the go-to word arrived in David Peoples’ rewrite of Fancher’s first draft of the film.

Location, Location, Location: Scott’s film presented such a visually arresting look at a futuristic Los Angeles, mixed in with mid-20th century aesthetic (art deco inspirations, the 40’s fashions most obvious in replicant Rachael’s hair and clothing) and film noir tones that recall Raymond Chandler’s stories. L.A. natives often remark that, as the city expands, it starts to feel more like Blade Runner all the time. So of course, lo and behold, that’s not where Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? takes place! Dick’s novel is set in San Francisco following World War Terminus (WWT), a nuclear conflict that wiped out most animal and human life, populated mostly by people with mental and physical defects due to fallout. (The better-off portion of humanity, as in the film, have moved away from Earth to the Off-World Colonies.)

(ElectricDynamite/Flickr)

The Fundamental Humanity of The Non-Human: Remember where I noted earlier that the theme that both film and novel explore is basically the same? That’s true, however Dick’s perspective in the book is quite different from what Scott, Fancher & Peoples came up with. In Dick’s book, his portrayal of the “andies” is that they are totally lacking in empathy, and this is what separates them from humanity; meanwhile, Blade Runner the film blurs these lines significnantly in how it conveys the “feelings” of replicants like Pris, and even the vicious Roy Batty. (Think about that; a Roy Batty incapable of experiencing any shred of human emotion would never be able to deliver the “tears in rain” monologue, let alone save Deckard’s life.)

(Warner Bros.)

Perhaps the best example of this is Rachael; in the film, she is a classic noir femme whose cool is ultimately shattered when the illusion she is human is ripped away from her, and discovering all of her memories are implanted makes her tragically sympathetic. Dick’s version of Rachael, meanwhile, is a heartless villain; she betrays the book’s Deckard, who has been saving up his money simply to buy a pet. Animals are incredibly rare and coveted in the novel’s tale, and so when our hero is finally able to purchase a humble goat to care for, the unfeeling Rachael kills the poor thing out of spite and a craving for attention.

(Oh, and by the way, animal ownership is also a status symbol such that humans sometimes buy robotic ones to maintain the illusion. Deckard, prior to the goat, owned an electric sheep. There’s your title folks. 😉 )

Oh, and there are more…: Many things about the book and novel are the same (the elite class of synthetic humans are called Nexus-6; the one way to tell human from android/replicant is the Voigt-Kampff test), and plenty are different (i.e. an entire subplot around a religion called Mercerism, using shared experiences to instill the principles of empathy, was dropped from the film adaptation). We probably shouldn’t break it down any further though, because both Dick’s novel and Blade Runner are indisputable classics that you should revisit immediately. No, like right now. Go!