Not every writer gets to do what they love professionally. It can be a long road to get there but Gary Whitta has achieved the dream. With a film debut starring Denzel Washington and multiple big credits under his belt (including Rogue One: A Star Wars Story), we discussed his journey, his writing process and more.

What is your screenwriter origin story?

What is your screenwriter origin story?

I grew up loving two things, video games and movies, so I’ve been extremely fortunate that I’ve had the opportunity to pursue both of my childhood hobbies professionally, first as a games journalist for many years and then as a screenwriter. I grew up in England but my games career brought me to California, and while I was there I started trying my hand at the screenwriting thing because I was now so much closer to the part of the world that made the kind of movies I loved growing up, stuff like Star Wars, Trek, [Battlestar] Galactica…you know, all the cool nerdy stuff.

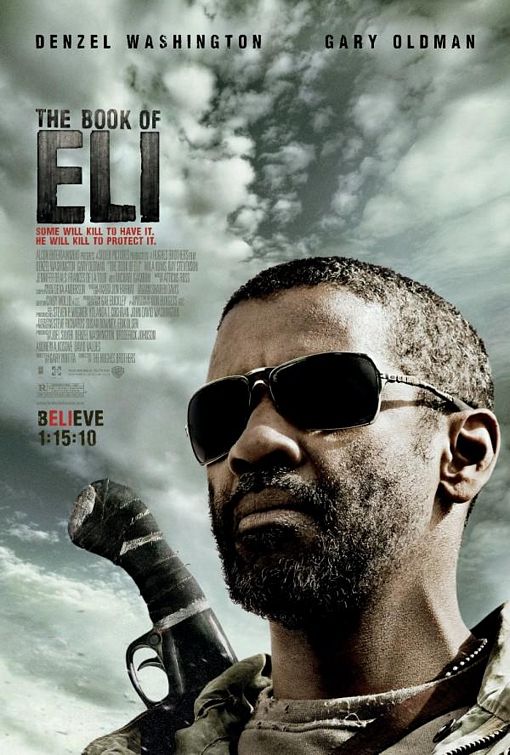

So I wrote a bunch of screenplays, each one slightly less terrible than the last, until I had one that I thought was good enough to show to people. That got me my first agent, and I sold my first screenplay shortly after that. I spent a while jobbing around in the industry, doing little rewrites and developing smaller films, until I wrote The Book of Eli, which was my first big studio movie. That script wound up on The Black List, which is a list compiled by movie industry professionals of their favorite scripts each year. Once we got Denzel [Washington] on board it became a real movie very quickly. So that one was kind of my big break, several years after I first started chipping away at the wall. Since then I’ve been fortunate enough to work on some really cool stuff, culminating in Rogue One, which has been the greatest privilege of my life.

You’ve written everything from videogames to movies. What, if any, are the differences between writing for different mediums?

I’ve done films, television, comics, novels, and video games. Of all of them I think videogames are by far the most difficult because we’re still learning how best to tell stories in that medium — we’re still kind of in the silent movie era. For something like The Walking Dead video game, which I helped out on, you’re not just writing one story but countless branching permutations that play out based on the choices the audience — the player — makes at every turn. It’s a lot of work just in terms of all the content you have to create, but also it can be a real pain to figure out how to make the story work in a satisfying way no matter what direction the player chooses to take it in. But when you can make that work it’s really satisfying for the audience because they feel that their version of the story is special and unique to them, not just the “one size fits all” story that’s the same for everyone in every other medium.

How does writing a script for an existing property or adapting a book differ from writing an original script?

I generally prefer to develop my own original ideas because there’s nothing more satisfying than creating your own characters and worlds out of thin air. But the reality is that getting original projects off the ground, particularly big expensive ones as sci-fi projects can tend to be, is extremely difficult. Hollywood loves franchises but it’s easy to remember that every billion-dollar franchise, be it The Fast and the Furious or Star Trek or Star Wars began with someone taking a risk on an original idea. When you’re developing your own original idea you’re the creator and you have the freedom to do whatever you like — at least until the people with the money to actually make it step in. But when you’re working on an existing property you have to remember that you’re a guest in somebody else’s house and to behave that way. You’re invited to bring your ideas and your contributions, but at the end of the day it doesn’t belong to you, you’re just being trusted to look after it for a while.

The Book of Eli and After Earth both have brand new worlds that are being introduced to audiences. What’s your method of world building and what’s your approach to getting viewers/readers to get invested?

Yeah, I’m really proud that my first two movies prior to Rogue One were both original ideas — in the case of Eli it was my original idea and in the case of AE it was Will Smith’s. As I mentioned, it’s tough to push an original movie uphill in Hollywood so any time you can get something totally new to the screen it’s a win. I think it’s an additional burden for genre writers, as along with the universal considerations of story and character you also have to find ways to communicate whatever different rules or mythology you’re creating. My instinct there is generally to throw the audience in at the deep end and let them find their way as you introduce the world a little bit at a time — that’s why Eli, for example, opens totally cold, with no explanation of where and when we are; the audience picks that up as we go along.

(Telltale Games)

(Telltale Games)

With a game like Telltale’s The Walking Dead, in which players can choose how the story plays out, how do you handle character development — especially with regards to a sequel?

Well we try not to let the player kill any characters that we might want to use in future installments, for one thing! A good example is Molly, a character who appears in the fourth episode of the first season, which I wrote. There’s a moment where she’s in trouble, fighting off a horde of zombies, and you have to try and save her, and there’s a scenario where you can fail. At one point that failure meant Molly died, but during development we decided we liked her enough that we wanted to keep her alive for possible use in future seasons, so we changed the “fail” ending so that Molly got left behind but you weren’t sure what really happened to her, we kept it ambiguous. I don’t know if she will ever crop up again but Telltale Games have that option because we left that door open.

Are there any other franchises that you’d love to expand the lore for?

Well one of them is definitely the amazing Mouse Guard graphic novels by David Petersen, and I’m lucky enough to be adapting them as a feature film for 20th Century Fox right now. Beyond that if I were ever given the chance to write something in the Star Trek universe I would jump at it. I’m actually working on a couple of things right now that fit into this category as well, but I’m not allowed to talk about them. Ha!

Who are some of your favorite writers?

My favorite screenwriters include Jon Spaihts and Eric Heisserer, who wrote two of the best movies of 2016 — Jon with Passengers and Eric with Arrival. Growing up I was in awe of Lawrence Kasdan, who wrote three of my favorite childhood movies, Raiders of the Lost Ark, The Empire Strikes Back, and Return of the Jedi. I got to meet him at the Rogue One premiere and it was probably the most starstruck I’ve ever been. My favorite authors are Kurt Vonnegut, Terry Pratchett, and — probably most of all — Douglas Adams. I honestly don’t know if I’d have a career as a writer without the inspiration I got from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

What inspires you?

Great writing. And more than anything, seeing great screenwriting succeed against all the odds in the film business. To go back to a previous answer, Passengers and Arrival are both tremendous scripts that struggled for years to make it to the big screen, but in the end they both did and with spectacular results. Great writing always wins in the end.

(Warner Bros. Pictures)

How do you propel yourself through a project?

The best thing you can do is choose your projects carefully. Writers don’t always have this luxury at the start of their careers, but it’s important to find the jobs and the projects that genuinely excite you creatively, not just things that will get you a paycheck. But even on the true passion projects it can be difficult — the work you most care about can cause you not just the most pleasure but the most pain. On every project there are times when you just want to bang your head against a brick wall. But when it’s going well, when the writing feels good, when it’s just flowing through you, it’s the best feeling in the world. Those moments of joy will always make the less fun parts worthwhile.

When you’re writing, do you mentally cast actors in the parts?

Sometimes, yeah, just so I can close my eyes and run scenes in my imagination. But with Eli, I never had anyone specific in mind. I was kind of amazed when we got Denzel, because I never for one moment thought we would get anyone on that level. After he came on board I worked with him to tailor the character more for him, and that’s the best luxury in the world because you no longer have to imagine an actor in the part, you know exactly who you’re writing for.

Any advice for aspiring screenwriters?

Write. Don’t make excuses, write. And finish what you write, it’s the greatest feeling in the world to get to FADE OUT or THE END, even if it’s just the first sloppy rough draft that’s going to need a lot of work. If you want to be a screenwriter, study great screenwriting. Find scripts on the internet — it’s easy to do nowadays — and read them. And don’t get too bogged down in reading how-to books or by screenwriting “gurus” who promise to know the secrets to writing a blockbuster. I promise you, they don’t.

Anything you’d like to plug? 🙂

I’m always happy to plug my novel, Abomination, which I’m very proud of. It’s kind of a gnarly mash-up of English medieval history and Lovecraftian horror, so you’ve got Vikings and war and magic and monsters all in the mix. You can find it at Inkshares.com or on Amazon and you can get the digital version for only a dollar!

Many thanks to Gary for taking the time to speak with us!